[Archive!] Pure mathematics, physics, chemistry, etc.: brain-training problems not related to trade in any way - page 14

You are missing trading opportunities:

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

Registration

Log in

You agree to website policy and terms of use

If you do not have an account, please register

Какие это такие запросы? Вы свой запрос перечитайте, запрос так запрос, - я на первом предложении то застрял, а развитие мысли "какие после каких бывают" добил меня окончательно.

PS: Жаль, что у Вас нет компаса. Хорошая штука - стороны света разные там показывает, направления всякие ...

Well, I have nothing to say, alas. :(

Ну мне сказать тут нечего, увы. :(

about the compass? - It's a joke, I thought it would suit your "psychotype". :о)

Алексей, тебя мое решение устраивает ?

Думаешь для 7-го это слишком круто (не общий, а частный случай 25 одноклассников) ?

Yeah, it's a bit steep for a 7. But it is elementary, which is nice.

Yurixx wrote(a) >> Two elements must have the same values.

It is not hard to check that with N=26 (i.e. there is no student with zero connections in the class), this repeated number = 13.

The only thing I don't understand is why 13 and not 14 or 2. You and your sequential partitioning procedure made my brain soften - but maybe that's where you should look for an explanation of why it's 13 :)

You used Dirichlet's principle, by the way, without naming it.

А почему так?

good question)

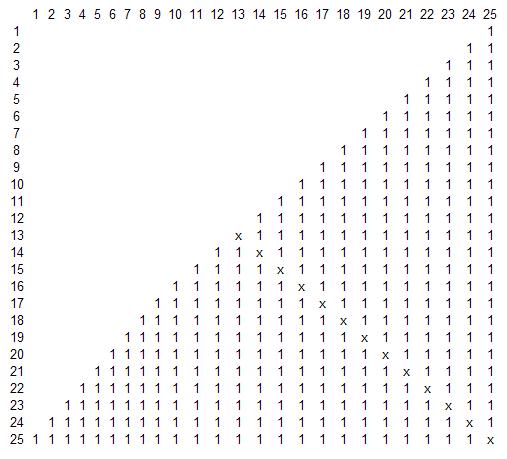

the picture is (from 1 to 25)

diagonal xxx, no one is friends with himself, it is necessary to do it Petya and so it is obvious thirteen times)))

in the case of zero to 24, you can ignore one classmate and get a square of 24*24 and 12 X's.

In the case of an odd-sized square, the diagonal = (N+1)/2, in the case of an even-sized one N/2.

You can think of it as the difference of friendships) in the class with and without Petya.

It doesn't sound like a rigorous proof. It's more of a finger-pointing illustration with no clear reason why exactly 12 or 13. OK, let's think about it.

The only thing I don't understand is why 13 and not 14 or 2. You and your sequential partitioning procedure have softened my mind - but perhaps that's where you should look for an explanation of why it's 13 :)

You used the Dirichlet principle, by the way, without naming it.

The point is that under this partitioning (and it obeys only one principle - everyone has a different number of friends, and therefore is quite general) Petya doesn't participate at all. He is one of 26 students, absolutely equal to the others. As a result, it turns out that everyone can not have a different number of friends - the series from 1 to N-1 can not be numbered consecutively N different numbers (it is in the final proof). Therefore, two students must have the same number of friends. And these two students are next to each other in the centre of the row. So it turns out that Petya must be one of these two. Only in this case everyone else has a different number of friends. Any other markings cannot satisfy this condition.

If you try hand-partitioning in the centre, you'll see for yourself.

Swan's table illustrates this.

I hope I understood your question correctly.

I think I didn't use Dirichlet's principle, but offered an elementary proof of its special case.

I personally loved it.

It's elegant.

It reminded me of the fable about the nimble little Gauss and the teacher who gave the class the task of adding numbers from 1 to 99 and was going to take off for a while - while the kids were adding.

They already knew multiplication, but repetition is the mother of learning...

Gauss fooled the teacher - the answer came right away.

;)

Swetten у нас самая дружелюбная.

:)

В коллективе из N сотрудников не может быть ситуации когда у каждого разное количество друзей

А вот если добавить - "у двух возможно одинаковое количество друзей" тогда нет проблем

Остается обозвать Петей одного из этих двух

Yes, that's almost right.

If you read the problem legally, then Peter MAY have the same number of friends as one of the others.

I told you - this problem is incorrect - by ANY reading of the conditions. I can probably prove it, and in various ways. But I won't..... yet.