The Latest Effort To Save The Eurozone Falls Flat On Its Face

The latest funding scheme designed to offer a boost to the eurozone’s banks is looking like a flop, after the release of initial figures on the take-up from the banks it's intended for.

The European Central Bank calls its latest wheeze "targeted long-term refinancing operations," or TLTROs. Banks can access cheap credit from Frankfurt and are allowed to take up to 7% of their total loans in the eurozone.

Figures out Thursday morning show that the bloc’s banks snagged €82.6 billion ($106.5 billion) in the long-term loans, less than basically anyone was expecting. Analysts are united, for once, in the view that the take-up of the scheme is a massive disappointment.

Kit Juckes, of Societe Generale, said in a research note Thursday morning that even a take-up of €100bn to €120bn would be “a small enough figure to leave many fearing that the ECB is still doing too little, too late."

Emily Nicol of Daiwa Capital Markets had similar sentiments, saying that any less than €100bn to €150bn “would cast some doubt on whether the TLTRO programme constitutes a fitting solution to the euro area’s economic challenges.”

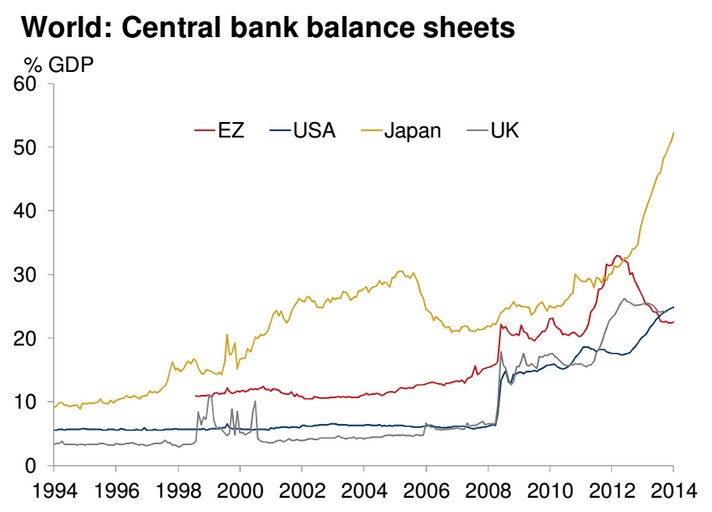

BNP Paribas economists twisted the knife, saying that ECB actions so far would be insufficient to raise the ECB’s balance sheet. The size of a central bank’s balance sheet is often used as a measure of how much monetary policymakers have eased policy for the economy. The ECB’s has been shrinking for some time. If its policies had been successful, the balance sheet would have grown — indicating it was successfully making new loans to banks that want them.

There will be another round of funding in December, but Jennifer McKeown of Capital Economics offered more pessimism in a note: “We can’t see why banks would borrow a lot more money then … We maintain our view that a broader programme of asset purchases, or quantitative easing, will be needed to get the economy going and avert the risk of deflation.”

sourceECB bank-funding programme sees low take-up

A European Central Bank measure designed to stimulate the flagging eurozone economy has seen a low initial take-up by banks.

The cheap loans for European banks have been designed to encourage lending to business.

But out of total loans of 400bn euros (£315bn) available on Thursday, only 82.6bn was taken up by 255 banks.

However, banks may be waiting for separate ECB measures due in October, analysts said.

Cheap loans to banks were part of a package announced in June designed to support lending and the economy.

The loans - called "targeted longer-term refinancing operations" (TLTROs) - see the banks pay 0.15% annual interest for up to four years.

Money market traders had been expecting banks to take up between 100bn and 200bn euros of TLTROs this week, with further interest in December, when banks get a second chance to apply for the cash.

Banks may be wary of taking up the loans before imminent ECB-led health-checks of the banking sector, said Karel Lannoo, chief executive of Brussels think tank the Centre for European Policy Studies.

"The European financial sector continues to be weak," said Mr Lannoo. "There may be a stigma because the markets are waiting for the AQR (asset quality review) in a few weeks."

However, banks may be waiting for details of a separate ECB programme to buy asset-backed securities, which are due out in October.

"We would warn about drawing too strong conclusions from the September round," said ABN Amro analyst Nick Kounis.

Visco Says ECB May Not Need to Add Stimulus Amid Euro Decline

The European Central Bank may not need to add stimulus measures after steps in the past three months pushed down the euro, said Governing Council member Ignazio Visco

“Inflation expectations have to be back where they were,” Visco said in an interview in Cairns, Australia, where he is attending a meeting of Group of 20 finance chiefs. “This doesn’t mean that there will be a next step. We have been bold enough to reduce interest rates to a level that was unexpected to the market.”

The single currency has dropped about 6 percent since early June, when the ECB introduced a negative interest rate on excess reserves and presented a four-year lending program to fuel credit. Policy makers reduced borrowing costs further earlier this month and committed to buying asset-backed securities and covered bonds to boost the ECB’s balance sheet by as much as 1 trillion euros ($1.3 trillion).

The extent of the exchange rate’s fall is “more or less, given the moves that were done between June and September, the right response,” said Visco, who also heads Italy’s central bank. The ECB isn’t targeting any exchange-rate level, he said.

One More Round Of Sanctions Could Send Europe Into Recession

Mohamed El-Erian, the chief economic adviser at Allianz SE , warned that global markets do not fully appreciate the risk posed by the Ukrainian crisis, a conflict which could push Europe into recession.

He saw few options to de-escalate tensions between Ukraine, its Western supporters and Russia, which has been accused of backing an insurgency led by ethnic Russian separatists.

In an interview at Reuters' New York headquarters on Monday, in which he also spoke about his controversial departure from Pimco earlier this year, El-Erian said just "one or at most two" more rounds of sanctions and counter sanctions between Russia and the West would likely push Europe into recession. That's especially true if Russia cuts energy supplies during the coming winter heating season.

"I think markets are underestimating Ukraine," El-Erian said. "It is very hard to find a solution that reconciles the three parties involved – Ukraine, the West and Russia."

El-Erian said markets also were placing "enormous faith" in the world's central banks, such as the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank. Through a series of experimental policy actions since the 2008 financial crisis, the world's largest central banks have gotten deeply into the "business of divorcing" asset valuations from fundamentals.

The space between what El-Erian sees as lofty valuations and more earthly fundamentals is "an air pocket" at risk of rapid collapse if markets are confronted with a jarring catalyst, such as Ukraine.

"I worry that the marketplace is paying very little attention to geopolitical issues, but they've done so for good reasons so far," he said. To date, investors have largely succeeded in navigating numerous brief bouts of market choppiness in the face of "geopolitical shock."

An endemic hazard arising from that is that investors want unambiguous evidence that "the turn" has occurred before they opt for a more defensive allocation, El-Erian said.

"The problem with that is that once you get that, everyone wants to get out. And at that point, you get the air pocket."

A respected investor who once ran Harvard University's endowment, El-Erian made waves in January when he resigned from Pimco, a unit of German insurer Allianz and an investment powerhouse with nearly $2 trillion of assets. There, he had been chief executive and had shared the role of chief investment officer with bond market guru Bill Gross.

The Standard & Poor's 500 Index and the Dow Jones industrial average have both hit records in recent weeks, gains he contends are emblematic of the disconnect between valuation and fundamentals.

Their performance is largely fueled by the Fed's actions, which have made other assets such as bonds even pricier by comparison, as well as financial maneuvering by corporations, which are spending cash buying their own shares or on mergers and acquisitions, he said.

Stocks, he said, are signaling "We are expensive, but we are cheaper than other things that are a lot more expensive."

El-Erian said Alibaba Group's record $29.7 billion initial public offering last week is one reflection that markets continue to have tremendous risk appetite because investors believe the Fed has their back.

That said, he believes the Fed is now out of sync with its peers, the ECB in particular, and will begin to raise interest rates toward the end of the second quarter of 2015, or sooner perhaps. Still, the Fed will not be inclined to raise rates rapidly after that initial move.

"I think the Fed will move slower and not as high as we've been historically used to," he said.

And, El-Erian said, if Europe goes in to recession, even the Fed's projected lift off from near zero interest rates, where it has held its policy rate since the end of 2008, would likely be off the table.

Draghi May Discover Weaker Euro Doesn’t Buy Enough Recovery

Mario Draghi may find a falling currency can’t buy much of an economic recovery.

The euro has dropped toward a two-year low against the dollar since the European Central Bank president boosted stimulus earlier this month. Economics textbooks say that should lift Europe’s struggling growth rate by boosting exports and speed inflation by raising import prices. Such effects will be more welcome if falling commodities deal a disinflationary blow.

It’s time for those textbooks to be revised, according to economists at Societe Generale SA led by Michala Marcussen, who reckon a devaluation of the euro will not be as stimulatory as it once was and perhaps as much as the ECB is hoping.

For one thing, the single currency may not be that weak yet. While it has fallen 7.5 percent against the dollar this year, it has slipped just 4 percent on a trade-weighted basis.

A deep decline may be hard to achieve. While the euro should keep falling against the dollar and sterling as the Federal Reserve and Bank of England shift toward higher interest rates, those currencies account for only about a third of the trade-weighted index.

The monetary policies of Japan and China are almost just as important, with the yen and yuan accounting for a quarter of the euro’s value, according to Marcussen. With their central banks also dovish, the euro may have less far to fall against those currencies, meaning a 10 percent decline on a trade-weighted basis would require the single currency to drop below $1.15 and 70 pence. It was at $1.28 and 0.78 pence today.

Long-Term Rate

Another brake on any descent is that the euro’s long-term rate may actually have risen since the global financial crisis to $1.35 from $1.31, Societe Generale calculates. That’s because in aggregate the euro area is running a current-account surplus and its budget deficit and debt are lower than in other major economies.

Even if the euro does hit the skids, changes to how economies operate mean it is less of a growth driver than it once was, according to Marcussen.

Reason one is that a weaker currency comes with lower borrowing costs, and while this should be good news, she worries that households, especially those in Germany, regard lower rates as a reason to save, not spend, to meet future needs.

Draghi The Dictator: "Working With The Germans Is Impossible"

The war of words between Europe's unelected monetary-policy dictator Mario Draghi and Germany's "but it's us that pays for all this" Bundesbank has been gaining momentum since Jens Weidmann penned his Op-Ed slamming Draghi's OMT 'whatever it takes' as "too close to state financing" in 2012. A week ago, Weidmann stepped up the rhetoric by claiming ECB policy is "hostage to politics" and has lost its indepdendence - warning Draghi's dictatorial policies were leading Europe down a "dangerous path." But now, as pressure grows from the Spanish (record unemployment, record bad debt, record low yields), Italian (record unemployment, record debt-to-GDP, record low yields) and French (record unemployment, treaty-busting-deficits, record low yields) for Draghi to monetize more assets, he has struck back in Focus magazine, blasting Weidmann is "impossible" to work with because the Germans "say no to everything." Dis-union...

Weidmann (2012): "When the central banks of the euro zone purchase the sovereign bonds of individual countries, these bonds end up on the Eurosystem's balance sheet. Ultimately the taxpayers of all other countries have to take responsibility for this. In democracies, it's the parliaments that should decide on such a far-reaching collectivization of risks, and not the central banks. Europe is proud of its democratic principles; they characterize European identity. That's something else that we should bear in mind."

Weidmann (2012): "The central bank is responsible for monetary stability, while national and European politicians decide on the composition of the monetary union. It wasn't the central banks that decided which countries are allowed to join the monetary union, but rather the governments."

Weidmann (2012): "I don't take my cue from the German government's position. That's part of being independent."

Weidmann (2012): "I want to work to make sure the euro stays as strong as the deutsche mark was."

Weidmann (2014): "There is a risk of monetary policy, especially in the euro area, being held hostage by politics,"

Weidmann (2014): "These concerns are particularly acute whenever the central bank buys specifically the most risky sovereign bonds... with government and corporate borrowing costs already super low, such a policy would have limited effect. Tying fiscal policies together through ECB bond purchases is a dangerous path."

And now Draghi responds... (via Focus Magazine)

The conflict between ECB President Mario Draghiand Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann over the course of the European Central Bank is more severe than expected, and has become “almost impossible,”

The Italian ECB chief characterizes the Bundesbank president after statements from witnesses internally on a regular basis with the three German words "No to all".

According to insiders, therefore Draghi is no longer even trying to win the Germans for its programs.

Since July there was a direct contact between the two presidents of the ECB and the Bundesbank outside of the two Council meetings in early September and early October.

* *

In other words, the Germans won;t let me do what I want - so I'm going to ignore them... this leaves the Germans with few options - none of them 'good' for a European Union.

Panic money-printing won’t save the eurozone

It sounds far-fetched, I know,” I wrote in this column in December 2007. “But the ultimate victim of this subprime crisis could be nothing less than the single currency’s existence”.

Reading it today, the above statement seems pretty reasonable. Many mainstream analysts now recognise the huge stresses imposed by the ongoing credit crunch could yet see monetary union break up, with at least one country leaving. To argue otherwise, certainly in Anglo-Saxon company, is to risk appearing in denial.

After the eurozone’s successive summer bond crises of 2011 and 2012, it’s no longer particularly controversial to accept what we sceptics have been warning about for years; that the “irreversibility” of monetary union is merely a political slogan.

A peripheral member-state could indeed leave of its own accord, or be forced out, so escaping the straitjacket of a vastly overvalued currency. Another may then opt, or be asked, to follow. Saying so is now part of reasonable economic discourse, not necessarily the start of a row.

The first time I wrote the words that begin this article, though, getting on for seven years ago, the situation was rather different. Back then, only “xenophobes” “cranks” and “nutters” argued the eurozone might not survive. The subprime meltdown, moreover, was seen as “America’s crisis”, for most French, German (and even British) observers a problem most definitely made on Wall Street.

It seemed weird, then, to suggest back in December 2007 that the most spectacular fallout from subprime – not only a severe market dip and related economic downturn, but something even more catastrophic, the forced break-up of vastly symbolic supranational structures – could actually happen in Europe.

It doesn’t seem weird now. Last week’s turmoil on global markets, which saw Greek bond yields pushed above an eye-watering 9pc, mean the eurozone crisis is back. As sovereign borrowing costs across several member states spiralled – not just Spain, Portugal and Italy, but France too – yields on 10-year German bunds plunged to an all-time low of 0.72pc, as panicked investors searched for safety.

Draghi is overseeing some difficult times, but he could end up being a MAJOR source of friction in the EU

Someone Didn't Do The Math On The ECB's Corporate Bond Purchasing "Trial Balloon"

While we understand that following the biggest market rout in years, it was all up to the central bankers to do everything in their power to restore confidence in the market's upward trajectory in a time when there are only 2 POMOs left under the Fed's soon ending QE3 program, which explains not only last week's 2 QE4 hints by FOMC presidents but also yesterday's ECB "leak" via Reuters that the central bank is contemplating launching corporate bond buying as soon as December. A leak which sent the market soaring to its best day of 2014. And while we give the European central bankers an A for effort, we can't help but wonder if someone did a major mathematical error when calculating the "bazooka impact" of yesterday's leak.

The reason: the same one we have cautioned about ever since 2012; the same why as we also explained in August the ECB's ABS QE will be grossly sufficient: Europe simply does not have enough eligible, unencumbered collateral in the private sector which can be monetized by the central bank (the same issue that the Fed itself was forced to taper QE once its holdings of 10 Year equivalents hit 35% as we showed last year and the TBAC started warning about gross bond market illiquidity). This goes back to a different issue, namely that Europe historically has funded itself on a secured basis, where the loans are kept on bank balance sheets (and serve as deposit collateral) unlike the US, where the primary source of corporate debt is through unsecured borrowing directly from lenders.

ECB QE would be about $5 billion monthly. Their salaries at the ECB are greater than that. That QE was just a threat

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

You agree to website policy and terms of use

The European Central Bank's (ECB) simultaneous announcement of an asset purchase program and cuts to its main interest rates should provide a strong message to European leaders: We have done all we can, now it's your turn.

The divergence of national economies within Europe, with the core (France, Germany, Netherlands) pulling away from the struggling periphery (Greece, Spain and Portugal), has meant that it has proven difficult for lower rates to translate into the higher bank lending needed to boost troubled economies. This has helped to exacerbate the underlying tensions within the monetary union and has begun to impact the health of the region's larger economies.

ECB President Mario Draghi explicitly stated that the asset purchase program, under which the ECB will purchase European asset-backed securities (loans pledged against a collection of assets) from the market, is being undertaken to get around these transmission problems.

Used in concert with the already announced Targeted Long-Term Refinancing Operation, whereby Eurozone banks can gain access to cheap funding from the central bank in return for higher lending, the idea is to get funding to small and medium-sized businesses that have languished as the Euro crisis has worn on.

In essence, however, this will mean that the ECB is promising funding to banks to create asset-backed loans that they will then purchase. If that sounds circular, it should.

And it has caused financial writer Frances Coppola to worry that the ECB is exposing itself to a big moral hazard problem:

[As] far as I can see, the SME ABS programme is either going to be too small to make much difference, or is likely to encounter serious problems with loan quality at some point, putting the ECB's balance sheet at risk.

(I highly recommend reading the full post)

As Coppola points out, while this scheme may be sufficient to help some healthy firms that have struggled to raise financing in recent years it relies heavily on a sharp increase in the supply of these types of loans. That, in turn, poses its own problems.

The quality of the loans are linked directly to the health of the underlying assets that they are pledged against. Within Europe, firms with the greatest potential to benefit from this scheme will be concentrated in already healthy economies in the core. So just as with interest rate cuts, the countries likely to benefit most are the same ones that are least in need of it.

Although Draghi pledged his commitment to "structural reform" within the Eurozone, he also repeated his call for a discussion on the overall stance of fiscal policy — suggesting he wants governments to ease up on their austerity programs and start spending again.

In his press conference following the rate cut announcement, Draghi dismissed talk of a "grand bargain" between fiscal and monetary powers in the monetary union. However, he did add "we all just have to do our own jobs." The implication is that Draghi has done his job and — short of entering the topsy-turvy world of aggressively negative interest rates — has no more weapons at his disposal. He needs governments to step in, too.

If I were Angela Merkel, I would read that as a challenge.

source