Neither Volkswagen, nor Greek story weakened the euro. Draghi's QE will fail as well.

The environment seems to be perfect for the euro to get lower: deflation is right around the corner, recent economic data pointed to a weak growth, and the European Central Bank (ECB) is expected to expand its QE program. However, the shared currency is hardly impacted by any of those. Traders are gradually losing faith ECB president Mario Draghi is capable of pressuring the euro.

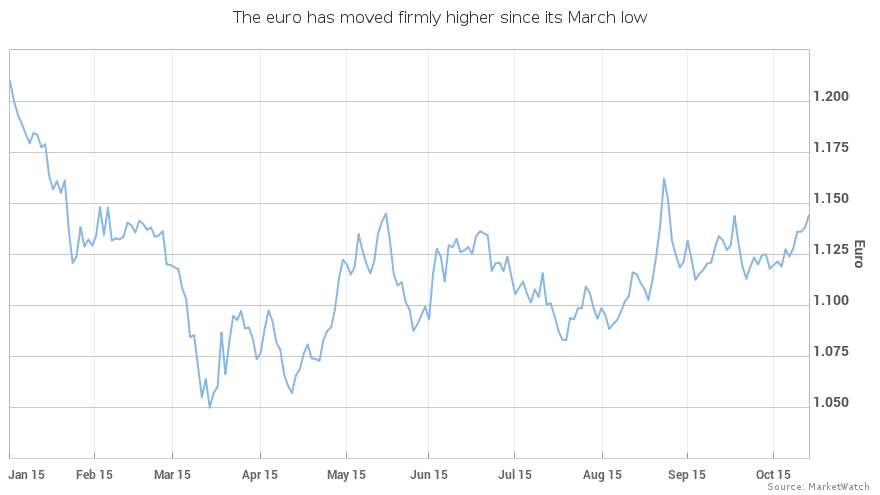

Throughout the last three months, the euro has climbed nearly 5% against the dollar to trade around $1.1440 and edged up 5.8% against the pound to £0.7425.

This is happening even after several analysts proclaimed the euro-dollar parity earlier this year. For HSBC, however, strengthening of the single currency has not become a surprise.

“If the euro can’t go down on the Volkswagen story, and the euro

can’t go down on the Greek story, it should be telling you something,”

said David Bloom, global head of forex research at HSBC, adding that the Federal Reserve is not as hawkish and the ECB is not as dovish as expected.

“The monetary-policy differential is actually closing and that’s favoring the euro.”

In late September, the banking institution raised its forecast for 2015 year-end on the euro to $1.14 from $1.05 and elevated its 2016 year-end forecast to $1.20 from $1.10.

Although many market participants expect the ECB to ease by the year-end and the Fed to hike rates in December, Bloom considers it will barely soften the euro, as these measures have already been largely priced in and the ECB is running out of large-scale easing options.

“We need some big stuff here for the euro to move. Not only do we not see that happening, we also think it’s not possible. There are some rules and regulations they set themselves that make it very difficult,” he said.

Jane Foley of Rabobank International agrees. She says markets will be surprised if the ECB to weaken the euro substantially.

Rabobank sees the euro falling to $1.09 by year-end, in line with the market consensus, though that’s up from its estimate of $1.06 at mid-year.

Simon Smith, chief economist at FxPro doesn’t see how more ECB easing would press the euro significantly lower like it did in March, when it hit a 12-year low around $1.05.

In early days of QE, it impacted currencies massively, he said. "But for the eurozone, because they came so late to the party, there’s a different relationship between QE and the currency. It’s pretty weak. It’s simply because of lower, diminishing returns. You’ll get less for the more you do something,” he noted.

The key ECB interest rate is already near zero, which has helped push German two-year bund rates substantially into negative, and it's difficult for them to shrink further.

“Already in some countries they are struggling to find bonds to buy. It would have to be even more unconventional means by which they undertake QE.”

Lower exchanges rates usually follow low interest rates, because it reduces the demand for the currency.